World Cup 1958 – Time for New Heroes

Kinshuk Biswas turns back the clock, to that year in the history of the FIFA World Cup, when the young Brazilians had the world at their feet

The World Cup host country for the year 1958 had been chosen as early as June 1950, during the FIFA Congress in Brazil held in conjunction with the World Cup finals. Sweden, Argentina, Chile and Mexico had shown interest in hosting the tournament. However, aggressive lobbying by the Swedes ensured that they ended up as the unanimous choice.

This was possibly the first tournament since 1934 without a clear favourite. The world had changed a lot in the four years since the last tournament. The all conquering Hungarian team had been left desecrated by the Soviet crackdown on the Hungarian revolution of 1956, prompting mass defection by the best players such as Ferenc Puskas, Sandor Kocsis and Zoltan Czibor. Nandor Hidegkuti and Jozsef Bozsik remained but were already past their best.

The defending champions West Germany still had Helmut Rahn and Hans Schafer and a dynamic young centre forward named Uwe Seeler. They lacked a creative playmaker in the midfield and so 37-year-old Fritz Walter was persuaded to come out of semi-retirement by the manager Sepp Herberger. The hosts, Sweden had credentials to match any of the top teams. Nils Liedholm and Gunnar Gren of AC Milan had been chosen although both were over 35 years of age. They had the famous English strategist George Raynor as manager but were an ageing team. Argentina was back after a 24-year absence and had both tremendous flair and pedigree, being the defending Copa America champions.

Unfortunately the three member forward line – Omar Sivori, Antonio Valentín Angelillo and Humberto Maschio had been poached by Italian clubs. Uruguay and Italy, the most successful nations in the World Cup till then had both failed to qualify after being defeated by Paraguay and Northern Ireland respectively.

Incidentally, all the four home nations of Britain – England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales had qualified; a feat yet to be repeated till date. All the teams had been hit by the Munich air disaster. Brazil was bringing a youthful team who had an unsuccessful tour of Europe in 1956. They were using a 4-4-2 formation which was still a work in progress. Soviet Union, the defending Olympic champions were making their debut with charismatic Lev Yashin in the goal. There were 16 teams in the final tournament and they had been divided into groups, and a draw was used on the basis of geographical location of the nations. There were four pots: Western Europe, Eastern Europe, British teams and the American continent. No Asian and African team participated. After the draw the four groups were:

|

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

Group 3 |

Group 4 |

|

West Germany |

France |

Sweden |

Austria |

|

Czechoslovakia |

Yugoslavia |

Hungary |

Soviet Union |

|

Northern Ireland |

Scotland |

Wales |

England |

|

Argentina |

Paraguay |

Mexico |

Brazil |

GROUP 1

The format was tinkered with yet again, with all teams playing each other in the group stage with play-off matches to decide progress in case the teams placed second were found to be tied on points. If the two top teams had tied, a draw of lots would decide the group champion. Some teams complained about fatigue due to play-off matches and FIFA decided to use goal averages of the teams to decide the positions. The Swedish FA rejected this proposal stating that the original format could not be changed. Of course, the extra revenue from the play-off matches was the main motivation behind the reluctance to accept the goal average system because the Swedish manager was the most vocal critic of the play-off system. However the goal average system was implemented in case the top two teams in a group had tied. All the rounds of group matches were played on the same dates, June 8, June 11 and June 15, with the exception of the Hungary versus Sweden match, which was played on June 12 instead of June 11.

The first match featured the match-up between the defending champions West Germany against the South American champions, Argentina. The Latin Americans started with an early goal by Oresto Corbetta in the third minute. After that, the non-existent marking of the Argentines made the match a Helmut Rahn show. Rahn had been persuaded by the manager to lose some weight by reducing his consumption of beer. He scored 2 goals with either foot from 25 yards out. Uwe Seeler added a third to give the champions a 3-1 victory. The second match was a major surprise with Northern Ireland defeating the Czechoslovakian team 1-0 with a headed goal from Wilbur Cush. In the second round of matches, Argentina played to their potential and whipped Northern Ireland 3-1.

It was a brilliant performance of skill and flair with the Latin Americans resorting to party trick dribbling and passing. The other match featured a typical comeback by the West Germans who fell behind by two goals to the Czechs only to claw back and earn a 2-2 draw. Although, it was with a controversial goal by Hans Schafer who was accused of barging into the Czech goalkeeper, Bretislav Dolejsi over the line in the 78th minute. Going into the last round of matches, all teams had an equal chance of qualification and danger of elimination. West Germany was the favourite going into the game against the Irish.

The Irish played their best game of the tournament and Harry Gregg, their goalkeeper made a string of outstanding saves even while hobbling and being unable to take kicks. The match ended 2-2. In the last match, Argentina was expected to overcome the dour Czechoslovakians. However, the match was the worst ever performance by their goalkeeper, Amadeo Carrizo – an all-time great.

The Europeans used their pace and superior movement to annihilate the Argentines 6-1; a result that eliminated the South Americans. The West Germans had topped the group but Northern Ireland and Czechoslovakia had to go to a play-off. The match finished 1-1 in regulation time and eventually Peter McParland scored the winner in the 97th minute to send the Irish into the quarter finals.

Group 2

The first match of the group was a goal-fest featuring France and Paraguay. The Paraguayans led 3-2 after the 50th minute. The French had a lot of quality in Raymond Kopa and Just Fontaine who went on to create five goals to give them a 7-3 victory. The other match featured Yugoslavia against Scotland, which was a hard fought 1-1 draw. The second round featured Paraguay against Scotland which was a thriller and ended in a 3-2 victory for the South Americans. The Yugoslavia-France match was an entertaining one of high quality football played by both sides. Fontaine scored two more goals for France but the East Europeans were a better organised side with some flair.

The Yugoslavians eventually overcame the French to register a 3-2 victory. In the last round of matches, the French required a victory against Scotland, and Paraguay required the same result against Yugoslavia. The Paraguayans played exciting football but were let down by poor defending to draw 3-3 with the Yugoslavians. In the France-Scotland match, the British team played their best of the tournament but ended losing by two goals scored by the unstoppable Fontaine. France and Yugoslavia advanced to the quarter finals with Paraguay ruing their missed opportunities and poor defensive display. France topped the group on goal average.

Group 3

The hosts played against the Mexicans in their opening match. The Swedes slowed down the pace of the play to suit their ageing side but still had enough quality to score three goals. With two from Agne Simonsson and a penalty converted by Liedholm, they emerged 3-0 victors. Hungary and Wales played out a 1-1 draw; a magnificently headed equaliser from John Charles in reply to an early goal by Jozsef Bozsik.

The Welsh goalkeeper, Jack Kelsey pulled off some great saves to deny the Hungarians. In the second round, the Mexicans avoided defeat for the first time in the tournament -a feat, which took them 9 matches and 28 years to achieve. They played out a 1-1 draw against Wales equalising in the 89th minute. The celebrations after the match were as if they had won the Cup itself. In the other match, Sweden defeated Hungary 2-1 with both ageing sides playing a slow tempo game, with both hosts’ goals coming through defensive lapses of the opposition. In the last round of matches, Sweden fielded a team of reserves against the Welsh to the indignation of the Hungarians. Eventually the match ended in a 0-0 draw, although Wales were lucky as the Swedes had some glaring misses. The Hungarians eventually made their presence felt with Hidegkuti having a great match against the Mexicans and easily winning 4-0.

Sweden qualified as group champions and a play-off was required between Hungary and Wales. The Hungarians mercilessly fouled John Charles, the best Welsh player. The match was played under a shadow of political tension as Imre Nagy, the leader of Hungarian uprising had been executed the day before. There were Hungarian immigrants and defectors in the stand chanting for a free Hungary with banners and posters. Amidst all this, the Welsh won 2-1 coming back from a goal down to reach the quarter-finals.

Group 4

![WC1958-F2-[TD]001](http://goaldentimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/WC1958-F2-TD001-255x300.png)

England played Soviet Union, against whom they had drawn a friendly in Moscow a few months back. In this match, the English were clearly second best against a side, with great fitness and good tactical acumen. Nikita Simonian and Valentin Ivanov put the Soviets 2-0 up.

However, England were given a lifeline by a freak Derek Kevan goal, which deflected off his head and wrong-footed the great Lev Yashin. The equaliser was a Tom Finney penalty after a contentious decision from the referee. A Bobby Robson goal was wrongly disallowed but at the end the English were relieved to have salvaged a point. The other match featured Brazil against Austria and defeated them 3-0 without much effort. Two goals were scored by Jose Altafini who was nicknamed Mazzola after the great Italian, Valentino Mazzola who died in the Turin air crash. The other goal was scored by Nilton Santos. The Brazilian coach, Vicente Feola however was not happy with his forwards, especially 19-year-old Mazzola, who he thought was weighed by his impending transfer to Italy.

The second round of matches featured a goalless draw between England and Brazil. Walter Winterbottom, the manager for England, put Bill Slater to man mark Didi, the focal point of Brazilian attacks.

![WC1958-F2-[TD]002](http://goaldentimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/WC1958-F2-TD002-226x300.png)

The English were lucky as Mazzola and Vava both hit the woodwork. In the other match, Austria dominated the Soviets for an hour and then Yashin saved a penalty. The Soviets started attacking the Austrian defence through the wings and Valentin and Aleksandr Ivanov (no relation) scored a goal each to set up a 2-0 victory. In the last round of matches, England were expected to easily defeat the Austrians but were pegged back to a 2-2 draw where they had to come from behind, twice. The Brazilian coach had brought a psychiatrist and asked him if he could play two new young players. The psychiatrist replied that one was too immature and infantile and the other so unsophisticated that his inclusion would be an absolute disaster for the team. Thankfully, Feola had very little faith in the doctor and played both the individuals: Pele, the infantile one and Garrincha, the unsophisticated one. The result was magical and they ripped a good Soviet team to shreds, setting up two goals for Vava in a 2-0 win. Brazil had topped the group but England had to play the Soviets in a play-off. The Soviets controlled the game and won by a 69th minute goal from Anatolyi Ilyin.

Quarter Finals

FIFA had got their quarter-final draw correct this time, featuring matches between group winners and runners up. Sweden played Soviet Union, France faced Northern Ireland, Brazil met Wales and West Germany was against Yugoslavia. In the match against the Soviets, the Swedish manager – George Raynor used a superb piece of tactics.

He knew that the opposition would mark his playmaker Liedholm. Hence, he made Gunnar Gren the playmaker for this match and Liedholm would draw away the marker. By the time the Soviets figured this out they were a goal down. They conceded another goal, late to give the hosts a 2-0 victory. France was too good for the Irish, defeating them 4-0 with Fontaine scoring another two goals. To be fair, the Irish were a team of walking wounded which was compounded by their team management making travel arrangements by bus instead of train, which entailed 12 hours of travel. The Brazil-Wales match was a very close affair. The Welsh were missing their best player, John Charles who was finally sidelined with all the incessant fouling of opponents getting the better of him. Jack Kelsey gave another magnificent account of his abilities and was beaten because Pele’s shot had been deflected off Stuart Williams. The Brazilians later admitted this was the toughest match they had in this tournament where they had scraped through 1-0. In the last quarter-final, West Germany beat Yugoslavia in a very dull affair with a spectacular goal scored by Rahn after dribbling past three defenders on the right wing.

Semi Finals

The hosts, Sweden played the defending champions, West Germany in a high voltage match. The West Germans took the lead through Schafer. The Swedes were lucky to equalise, as in the build up, the ball was clearly controlled by the hand of Liedholm. The match changed when Fritz Walter went off after a crunching tackle from Sigvard Parling. Immediately, Gunnar Gren freed from the clutches of Walter, scored in the 80th minute to give Sweden a 2-1 lead. West Germans went a man down when Erich Juscowiak was sent off. Kurt Hamrin scored the third Swedish goal to take the hosts to the final. In the second semi-final between Brazil and France, goals were inevitable with the attacking prowess of both sides. Vava put the Brazilians ahead in the second minute only to have Fontaine equalise in the ninth. After that, it was all Brazil with a goal from Didi and a Pele hat-trick in the second half. France pulled one goal back but the Brazilians were an emphatic 5-2 winners. In the third place match, France defeated West Germany with four goals from Just Fontaine, all being created by the talented Raymond Kopa. The final score was 6-3. Fontaine finished with 13 goals in the tournament- a record yet to be equalled.

Final

![WC1958-F2-[TD]003](http://goaldentimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/WC1958-F2-TD003-300x148.png)

The final match was played between the oldest (Sweden) and the youngest (Brazil) sides of the tournament. George Raynor, the Swedish coach had predicted that Brazil would panic if they could be made to concede an early goal. He got his wish as Simonsson received the ball from the defence, wide on the right in the fourth minute. His square pass found Liedholm, who went past the opposition defenders Orlando and Hilderaldo Bellini and beat Gilmar, the goalkeeper with a low grounder past his right hand (0-1). Instead of panicking, the Brazilians were eager to restart the game, which gave a feeling to Raynor that his pre-emption about the opposition may not be accurate and that his ageing stars could face problems.He was proved correct in the ninth minute when Garrincha went past his marker and tapped in a cross from the right which was lunged in by Vava (1-1). The repeat of the same move – a higher cross from Garrincha in the 32nd minute – beat the goalkeeper rushing out and was turned into the back of the net by Vava (2-1). The age of the Swedes was showing. Gunnar Gren was 20 years older than Pele which was evident and very painfully so! Pele hit the post from 20 yards in the 40thminute.

![WC1958-F2-[TD]004](http://goaldentimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/WC1958-F2-TD004-300x144.png)

The second half brought no respite for the Swedes. Pele scored a great goal in the 55th minute when from a Nilton Santos cross he went past defender Sigge Parling with a chest trap, and flipped the ball over the goalkeeper, Karl Svensson volleying it into the net (3-1). Mario Zagallo scored from a header in the 68th minute, beating his marker (4-1). Liedholm managed to create a goal for Simonsson, to reduce the margin (4-2). The final word in the match was written by Pele who back-heeled a ball to Zagallo on the left and moved forward between the defenders and hit a looping header over the goalkeeper into the net (5-2).

It was the exclamation point of an excellent tournament, which was won by the best side playing the best football. The Brazilians did a lap of honour around the stadium with the Swedish flag, as the crowd cheered equally loudly for them in spite of having the home team as opponents. It was a spectacular tournament with high-quality football and the ushering in of two young stars in the modern age of football.

![WC1958-F2-[TD]005](http://goaldentimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/WC1958-F2-TD005-193x300.png)

![WC1958-F2-[TD]006](http://goaldentimes.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/WC1958-F2-TD006-300x165.png)

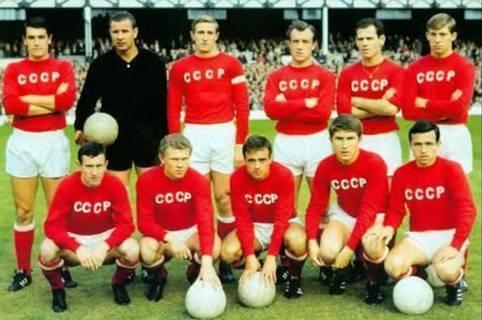

Lev Yashin: Russia: Dinamo Moscow : 1954 – 1967

Lev Yashin: Russia: Dinamo Moscow : 1954 – 1967 Rinat Dasayev: Russia: Spartak Moscow: 1979 – 1990

Rinat Dasayev: Russia: Spartak Moscow: 1979 – 1990 Vladimir Bessonov : Ukraine: : Dinamo Kyiv: 1977 – 1990

Vladimir Bessonov : Ukraine: : Dinamo Kyiv: 1977 – 1990 Anatoliy Demayanko: Ukraine: Dinamo Kyiv: 1981 – 1990

Anatoliy Demayanko: Ukraine: Dinamo Kyiv: 1981 – 1990 Revaz Dzodzuashvili : Georgia: FC Dinamo Tbilisi: 1969–1974

Revaz Dzodzuashvili : Georgia: FC Dinamo Tbilisi: 1969–1974 Evgeny Lovchev : Russia : Spartak Moscow: 1969 – 1977

Evgeny Lovchev : Russia : Spartak Moscow: 1969 – 1977 Albert Shesternyov: Russia: CSKA Moscow : 1961 – 1971

Albert Shesternyov: Russia: CSKA Moscow : 1961 – 1971 Aleksandr Chivadze: Georgia: FC Dinamo Tbilisi: 1980–1989

Aleksandr Chivadze: Georgia: FC Dinamo Tbilisi: 1980–1989 Murtaz Khurtsilava : Georgia : FC Dinamo Tbilisi: 1965 – 1973

Murtaz Khurtsilava : Georgia : FC Dinamo Tbilisi: 1965 – 1973 Vasily Rats: Ukrraine : Dinamo Kyiv: 1986–1990

Vasily Rats: Ukrraine : Dinamo Kyiv: 1986–1990 Valeri Voronin: Russia: FC Torpedo Moscow: 1960 – 1968

Valeri Voronin: Russia: FC Torpedo Moscow: 1960 – 1968 Igor Netto : Russia: Spartak Moscow: 1952 – 1965

Igor Netto : Russia: Spartak Moscow: 1952 – 1965 David Kipiani : Georgia : FC Dinamo Tbilisi: 1974-1981

David Kipiani : Georgia : FC Dinamo Tbilisi: 1974-1981 Volodymyr Muntyan : Ukraine: Dinamo Kyiv: 1968–1976

Volodymyr Muntyan : Ukraine: Dinamo Kyiv: 1968–1976 Oleksandr Zavarov : Ukraine: : Dinamo Kyiv: 1985–1990

Oleksandr Zavarov : Ukraine: : Dinamo Kyiv: 1985–1990 Yuri Gavrilov: Russia: Spartak Moscow: 1978–1985

Yuri Gavrilov: Russia: Spartak Moscow: 1978–1985 Sergei Ilyin: Russia: Dinamo Moscow: 1936-1939

Sergei Ilyin: Russia: Dinamo Moscow: 1936-1939 Khoren Oganesian: Armenia: Ararat Yerevan: 1979–1984

Khoren Oganesian: Armenia: Ararat Yerevan: 1979–1984 Alexei Mikhailichenko: Ukraine: Dinamo Kyiv: 1987–1991

Alexei Mikhailichenko: Ukraine: Dinamo Kyiv: 1987–1991 Eduard Streltsov: Russia : FC Torpedo Moscow: 1955–1968

Eduard Streltsov: Russia : FC Torpedo Moscow: 1955–1968 Valentin Ivanov: Russia: FC Torpedo Moscow: 1956 – 1965

Valentin Ivanov: Russia: FC Torpedo Moscow: 1956 – 1965 Mikheil Meskhi : Georgia: FC Dinamo Tbilisi: 1959–1966

Mikheil Meskhi : Georgia: FC Dinamo Tbilisi: 1959–1966 Igor Belanov : Ukraine: : Dinamo Kyiv 1985–1990

Igor Belanov : Ukraine: : Dinamo Kyiv 1985–1990 Oleg Blokhin: Ukraine: Dinamo Kyiv: 1972–1988

Oleg Blokhin: Ukraine: Dinamo Kyiv: 1972–1988 Grigory Fedotov : Russia: CSKA Moscow: 1937–1945

Grigory Fedotov : Russia: CSKA Moscow: 1937–1945 Viktor Ponedelnik : Russia: SKA Rostov-on-Don: 1960–1966

Viktor Ponedelnik : Russia: SKA Rostov-on-Don: 1960–1966 Igor Chislenko: Russia: Dinamo Moscow : 1959 – 1968

Igor Chislenko: Russia: Dinamo Moscow : 1959 – 1968